Abrasives

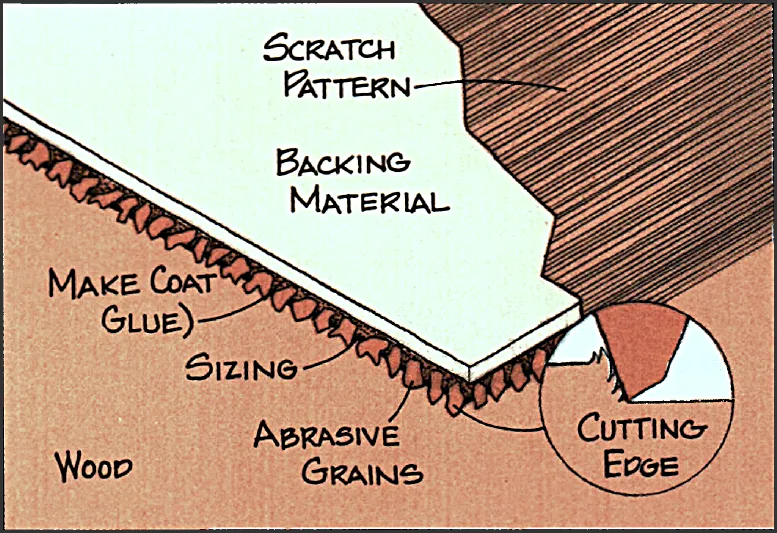

Sandpaper and other abrasives are scraping tools, consisting of hard sand-size minerals attached to a cloth or paper backing. Each grain has sharp edges that scrape the wood’s surface, removing a small amount of stock. As they do so, they level the rough and uneven spots on the surface, leaving a uniform scratch pattern – a series of tiny grooves cut by the grains. The smaller the grains, the finer the scratch pattern, and the smoother the sanded surface appears to be. The size of the abrasive grains is graded on a system of grits.

A dozen or more grits are commonly available at most home centers, hardware stores, and automotive supply stores. More can be purchased online. You can also find different types of abrasives mounted on different backings, some with different coatings and different ways to mount them on your tools. The material you are sanding, the tools you are using to sand, and what you hope to achieve by sanding determines what kind of abrasive, grit, backing, coating and mounting you should use.

The cutting edges of abrasive grains leave a scratch pattern on the wood. These grains are adhered to a backing material with a "make coat" of glue, and covered with a sizing.

ABRASIVE MATERIALS

Four types of mineral sand are commonly used in woodworking.

Garnet is preferred for hand sanding because it's very sharp and stays that way. The mineral is not particularly hard, but the grains fracture as you use them, constantly creating new cut ting edges. This tendency to fracture is referred to as friability.

50 grit garnet sandpaper at 30x magnification

Aluminum oxide is made by fusing bauxite in an electric furnace. It’s not particularly friable, but although it dulls eventually, the cutting edges are very sharp and durable. For this reason, it's used for machine sanding.

60 grit aluminum oxide sandpaper at 30x magnification

Silicon carbide is made by heating silica and carbon. The color indicates its application – black or charcoal for wet and dry sanding; light gray for dry sanding only. It’s very friable. Silicon carbide is preferred for sanding finishes between coats or rubbing out the final coat.

80 grit silicon carbide sandpaper at 30x magnification

Alumina-zirconia (erroneously called "zirconium") is an alloy of aluminum oxide and zirconium oxide. It's an extremely tough abrasive, and is typically used for heavy-duty surfacing operations such as thickness-sanding. It’s moderately friable; the grains fracture to produce new cutting edges, but only under extreme pressure.

80 grit ceramic sandpaper at 30x magnification

There are also a wide variety of ceramic abrasives you might consider. In fact, alumina zirconia is technically a ceramic, but there are many other materials that manufacturers can use to make this stuff, and they may not tell you what it is. The abrasive will simply be labeled “ceramic” without disclosing the materials. This keeps the recipe proprietary.

Also be aware that abrasive manufactures are constantly upgrading their materials and creating new ones for different purposes. New or old, it always helps to know something about the abrasive material, what it’s designed to do, and how it differs from your other choices.

ABRASIVE GRADES

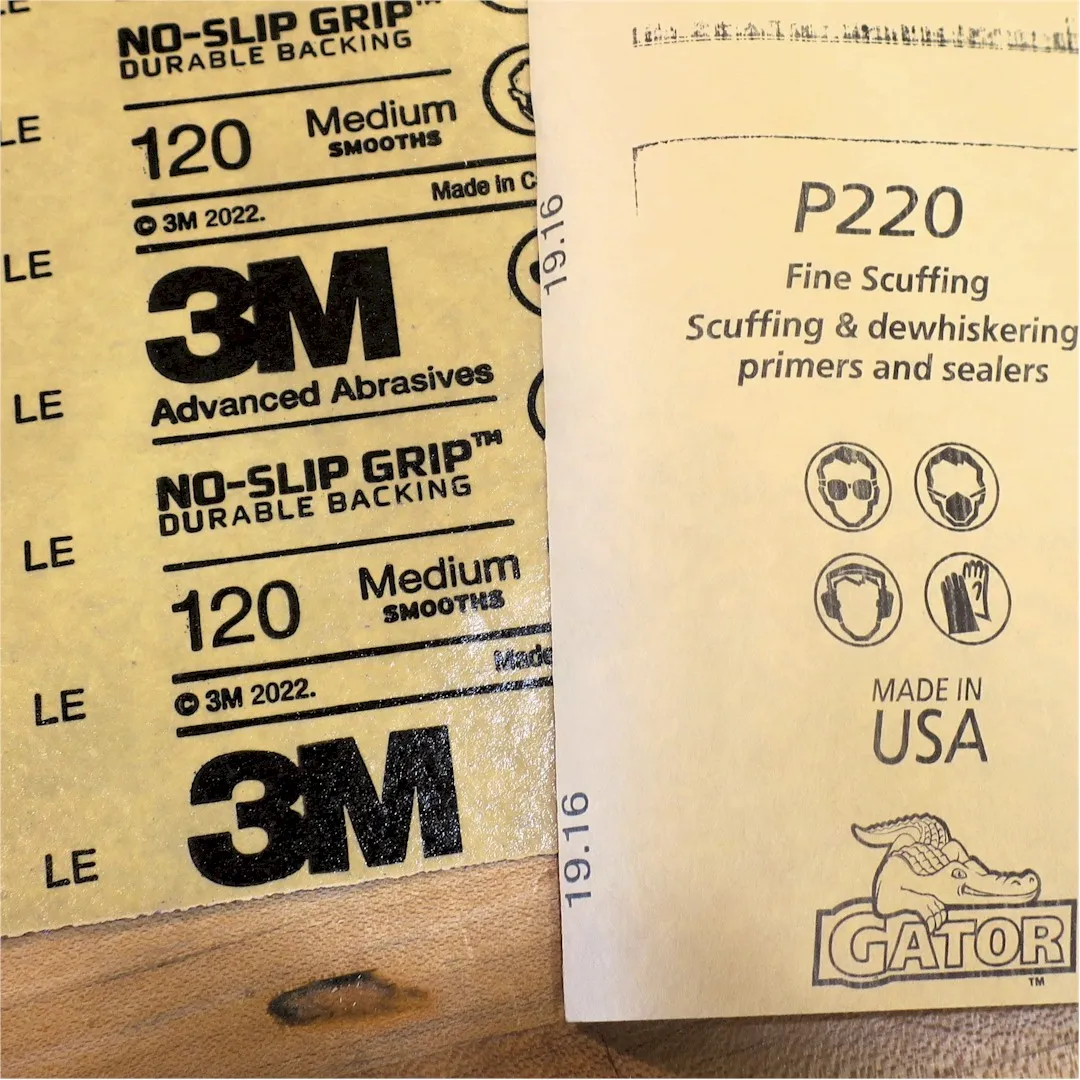

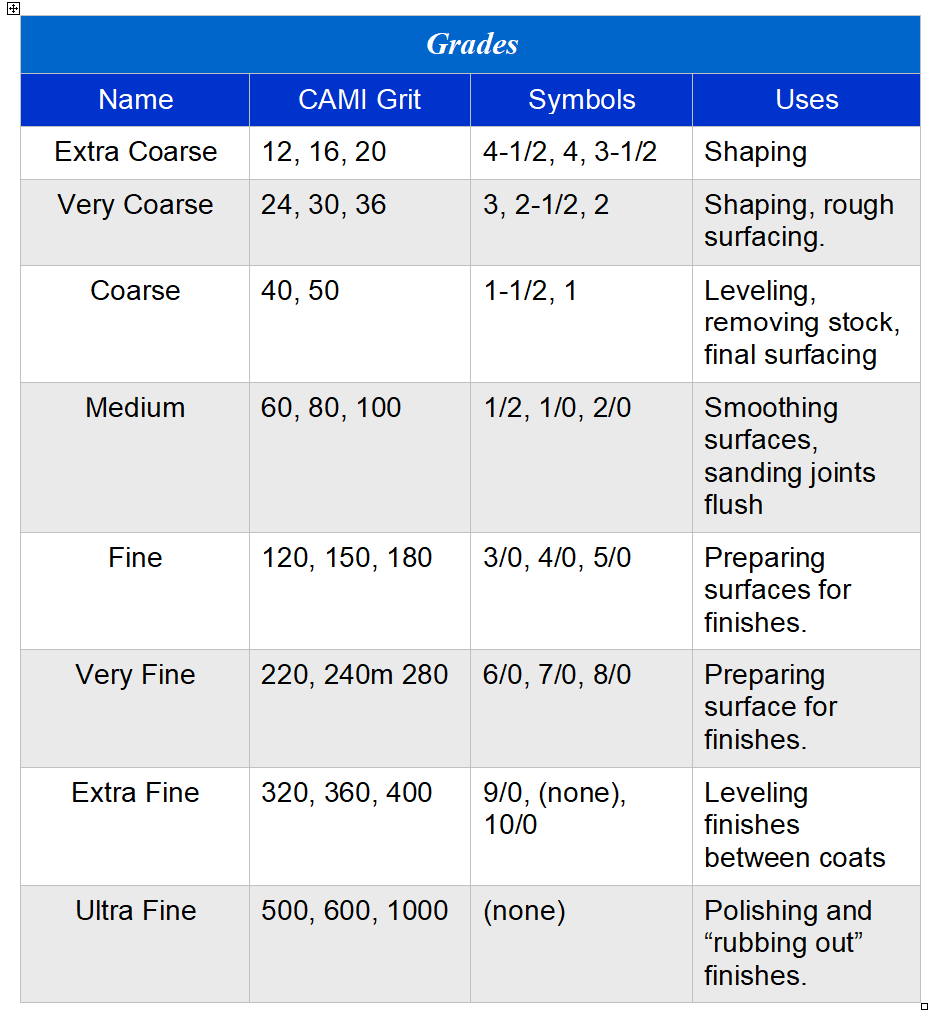

Abrasives are graded according to the grain size or grit by sifting them through progressively finer sieves. If a grain falls through a sieve with 80 openings per inch, but won't fall through the next smaller sieve, it's considered to be 80 grit. This is called the CAMI grit system, and it’s used mostly in the United States. In Europe and elsewhere, craftsmen commonly use the FEPA system. FEPA numbers are based on the actual size of the abrasive particles and are more exacting than CAMI. For this reason, it’s preferred for applications needing precise surface finishes. You’ll know you’re looking at a FEPA grit number if it’s proceeded by a “P.” as in P80.

The CAMI grit is simply shown as a number, FEPA grit is proceeded by a "P."

There are also less precise grading systems. Manufacturers may simply assign each grit a name (coarse, medium, fine, and so on), and these vary widely from brand to brand. There is also a much older system of abrasive symbols that is still in use. It runs from an extra coarse “4-1/2” to an ultra fine “10/0.”

American hardware stores offer a wide selection of abrasive grades, from 50 to 600 grit (on the CAMI system). For most woodworking tasks, you don't need anything coarser or finer than this. But if you do, abrasives from 12 to 1200 grit are commonly available online. And some automotive and aviation supply houses sell abrasive materials up to 12,000 grit!

You will commonly need more than one grit size. If you are sanding to smooth a surface, you must use consecutive grades of sandpaper, working your way from coarse to fine to achieve the degree of smoothness you’re after. Remember that the grains create a scratch pattern on the surface. The larger the grain (the coarser the grade), the larger and deeper the scratches will be.

When you move to the next finer grade, you trade the previous set of scratches for slightly smaller ones. If you jump grades – move to a much finer grit -- the fine abrasive grains may be too small to level the larger scratches without a great deal of work. – think about what it would be like to level a mountain with a garden spade. As a result, the surface will be left with an uneven scratch pattern, with deep scratches among the fine ones. Because these deep scratches fill with fine sanding dust, they may be nearly invisible to you until you apply a finish to the wood. Then the finish will darken the torn end-grain fibers in the deep scratches, making them stand out from the surrounding wood surface. This may ruin the smooth and consistent appearance of the surface.

Sand with consecutively smaller grits to maintain an even scratch pattern; skiping grits may leave grooves. However, you can make bigger jumps between grits when machine sanding than when hand sanding. How big? Depends on the tool, the abrasive, and the wood -- only experience will tell.

BACKING MATERIAL

The abrasive can be glued to either cloth (a cotton/polyester blend) or paper. Of the two, cloth is more durable. It comes in two weights. Thicker "X" backings are for heavy machine sanding; thinner "J" backings are for light-duty machine sanding and hand sanding. Cloth is also impervious to water, and can be used for wet-sanding.

Paper backings come in several weights, from "A" (lightest) to "F" (heaviest). Generally, the lighter papers are used for finer grits, and the heavier papers for coarser grits.

Paper backings on the left show "C" and "D" weights. Cloth backings on the right show "J" and "X" weights.

FYI – Ever wonder why paper-backed abrasives curl up? For the same reason that a board will cup if you only apply a finish to one face. The resin that adheres the abrasive to the paper acts like a finish, creating a barrier to moisture. The uncoated side of the paper, however, absorbs and releases moisture with changes in relative humidity. The fibers on the uncoated side swell, while the other side barely moves. This difference in movement causes the paper to curl.

You can prevent curling by storing your sandpaper between small weighted sheets of plywood, partical board, or hardboard.

COATING

All abrasives are available in two coats.

- Open-coat sandpapers have abrasives applied to just 50 to 70 percent of the surface. They don't load easily; the open spaces enable the paper to clear itself of dust.

- Closed-coat papers are covered completely. Because there are more cutting edges per inch, they cut fast. However, when sanding soft or resinous surfaces, sawdust packs between the grit and loads the paper.

Open coat 100# aluminum oxide on the left; Closed coat 100# garnet on the right.

Sandpapers sometimes have zinc stearate coatings, a chemical treatment that prevents sawdust from sticking to the abrasive and loading the sandpaper. They are often labeled as “no load,” “no fill,” and “non-clogging.” While these coatings are effective at slowing the loading, they often rub off on the wood and may interfere with some finishes.

MOUNTING

Some abrasive papers are self-mounting so that they can be easily attached to sanding tools, especially pads and discs. The most common and least expensive mounting system is pressure sensitive adhesive, or PSA. This adhesive is applied to the backing of the sandpaper and protected with release paper. To mount a PSA-backed abrasive, peel off the release paper and press the sandpaper onto the pad or block. The harder and longer you press, the better the sandpaper will adhere. Note: PSA paper is also temperature sensitive. If the surface you want to stick it to is too cold, it may not stay. It helps to gently warm the surface with a heat gun. It also helps to clean the surface with mineral spirits or naptha to remove all of the old adhesive.

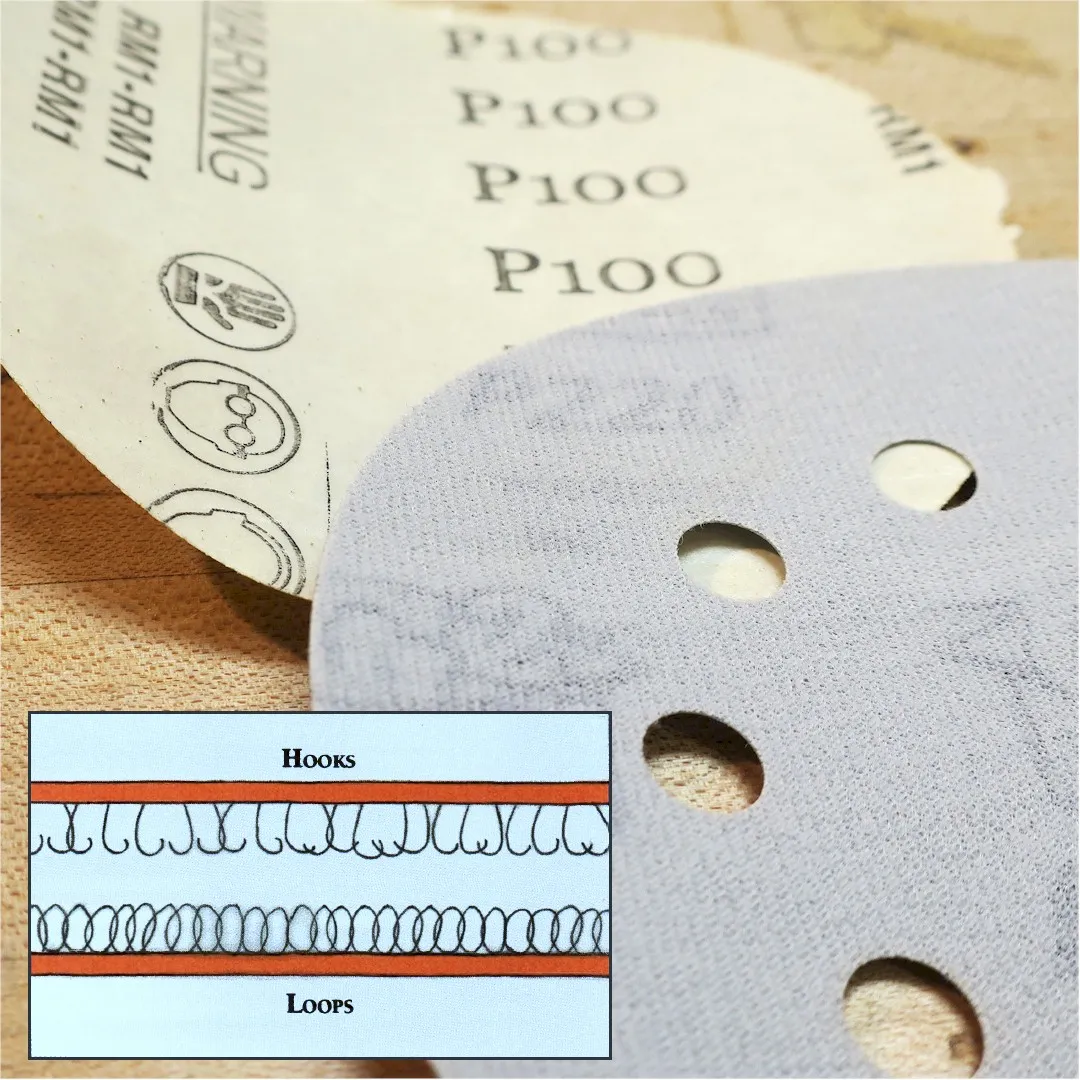

Other self-mounting abrasives use a hook-and-loop system. The surface of the pad or block has hundreds of tiny hooks that fasten to the fiber loops on the back of the sandpaper. To mount the abrasive, just press the hooks and loops together. This system is more expensive than PSA, but changing abrasives is much easier. You can also re-use hook-and-loop abrasives, mounting and remounting them many times. You can only mount PSA sandpaper once.

Additionally, hooks and loops better conform to curves. PSA wants to remain flat, and is best used when you need to level a surface.

The most common methods for mounting a sanding disc to a pad is either pressure sensitive adhesives (PSA - top) or hooks and loops (bottom).

Charts

SUPPORT US

If you enjoyed the article and want to ensure we make more on other topics, you can support us by purchasing Nick's books and project plans at the Workshop Companion Shopify Store. And — as always — thank you for your kind attention.

Back to Top